7 interesting facts about knights

They played tennis

The Book:

The Knight in History

By Frances Gies

Harper Perennial

1984

The Talk:

In her 1984 book The Knight in History historian Frances Gies traces the rise, fall, and legacy of knighthood in Europe. Some chapters deal with broad historical trends, while others focus on specific knights that exemplified knighthood and its transformation over time. Here are some of my favorite parts from the book:

1. Primogeniture shaped the development of knighthood in important ways.

Prior to primogeniture, land was divided up into equal parts with each new generation. This meant that in a couple generations family wealth was broken up into tiny fractions of land. Primogeniture solved that problem, while creating new ones. First and foremost, what to do with all the other siblings. Sons of landed knights that weren’t going to inherit anything had basically two main tracks: church or war. The image of the “knight errant” wandering through the wilderness with his squire was a direct result of primogeniture.

In addition, these free knights were available to leave Europe for the Crusades—driven by the possibility of gaining land—and it was surely a factor in the movement’s size and popularity.

2. Lords competed for knights by adding perks and lowering obligations.

One of my biggest takeaways from Gies book is that the feudal system was messy, complicated, and changed a lot over time. Some regions became far more feudalized than others. Some knights had land, some didn’t. Most knights held fiefs from multiple lords, each under different negotiated terms. Enemies would often try to win over opposing knights with bribes. And lords in an area would compete to offer the most favorable terms to a knight.

In my mind I had pictures of the knight kneeling before a lord, pledging his life and honor, but it sounds a lot more like a business transaction—and it became increasingly so as centuries progressed.

3. Troubadours were knights.

Another picture I had in my head was of a troubadour as nothing more than a poor wandering bard. This was incorrect.

The troubadours were knights, as were their successors, the trouvéres of northern France and and the minnesingers in Germany.

They were fighters, and they crafted songs in complex rhyme scenes (likely borrowed from or in imitation of Spanish Muslims) that told of their valor and exploits. They also sang of romance, of their unrequited love for the wives of lords.

Earthly love had one invariable characteristic: it was adulterous. The object was always a married woman. With equal invariability her status was always higher than that of the poet, who approached her humbly and worshipfully, eager to “serve.”

The earliest knights in the 900s and 1000s were not yet entirely part of the noble class. They were considered the bottom of nobility or the top of the peasantry. Financial fortunes often put people into knighthood or out of it. By the 12th Century, when the troubadours flourished, they were moving more into nobility — and perhaps that’s part of the knight’s mystique and the troubadour’s ambiguous-transgressive pose.

4. The Middle Ages kept running out of knights because nobody wanted to be one.

Being a knight was expensive. Knights were expected to provide their own armor (which was very expensive), maintain their own horses, squires, etc. Many knights fell into poverty and simply couldn’t afford to continue. When, in the 13th Century, knighthood became hereditary, many heirs elected to not become knights.

From the middle of the century, squires multiplied until they were more numerous than knights.

Kings actually had to enforce knighting on those who could afford it in order to have knights available for war. The problem only seems to have grown worse as the centuries went on. The ubiquitous “esquire” at the end of names denoted this position of being in the knight class but not being a knight (a “sir”).

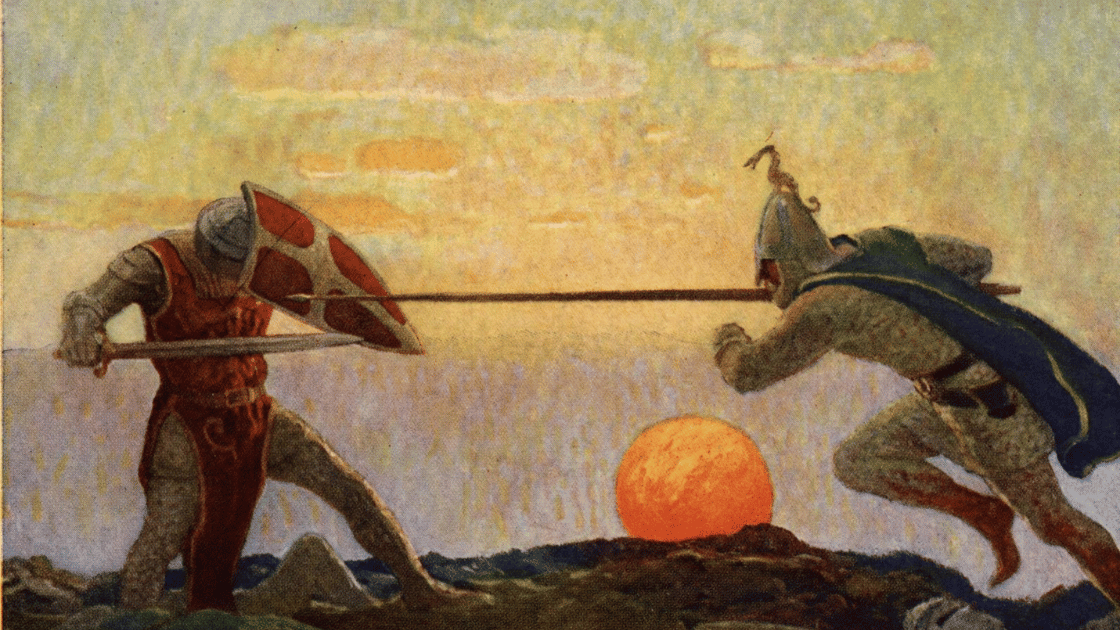

5. Scorched earth warfare was more common than chivalry.

My layperson understanding of the origin of knights goes like this: In the Middle Ages, owning a horse and armor and a sword was expensive. Very few people could afford it. Thus, if you could, you could basically run through the countryside and do whatever you want and nobody could stop you. The earliest knights were basically local bandit warlords.

The Church stepped in (because its churches and monasteries were being robbed and terrorized) and tried to use its spiritual leverage to curb the excesses of these lawless horsemen. The Peace of God and the Truce of God tried to put some boundaries on who knights could terrorize and when. Eventually, the Church sacralized the “dubbing” of knights, making a Church-sanctioned ritual to try and get knights to vow to protect the weak rather than rape and pillage them.

It is clear that this ideal remained throughout the Middle Ages. It is not clear that it was followed by even a fraction of actual knights. Even in the 14th and 15th Centuries, when knights received regular pay, they would frequently perform a chevauchée through the countryside kidnapping anyone they could ransom, killing anyone they couldn’t, stealing everything of portable value, and setting the rest on fire.

Guides for chivalry, across the centuries, seem to plead with their readers: Please don’t be like most knights these days. Please don’t hurt innocent people. That’s not what real knights do. (i.e. that’s what real knights do)

6. The Knights Templar were a moderating force on the Crusades.

In the early days of knighthood, there were no “orders” of knights. Every knight was an independent warrior. If you saw them from afar, each one would be wearing different colors. In combat, they did not wait for orders. They just attacked whenever they personally felt like it.

It was only with the Crusades that knightly orders were created. Orders of knights combined monastic rule with warfare. The three orders that Gies outlines are the Temple, Hospital, and Teutonic orders. Unlike everybody else, if you saw them from afar, they would all be wearing the same colors. Also, unlike everybody else, they obeyed their superiors. They were disciplined units. This made them far more effective and powerful than other knights of their day. The Temple and Hospital orders set up castles across the Holy Land, and they served almost like tour guides for Europeans who wanted to have a “Crusade experience.”

The Templars, living permanently among the Saracens, were far more realistic about the military situation than European visitors. They negotiated diplomatic treaties, and they often waved off European lords who wanted to capture certain cities. For this reason, Templars were sometimes looked at with suspicion in Europe as having “gone native” and being far too friendly with the enemies of God.

7. Knights played tennis.

Gies opens a story about one of the most famous knights of the 14th Century this way:

[Betrand] Du Guesclin joined a small relief force gathering at Dinan, northeast of Rennes. He was watching companions playing a game of tennis when he received word that his younger brother Olivier, had been treacherously made prisoner during a truce.

Tennis is way older than I knew! I suppose I knew Henry VIII played tennis in the 1500s, but this was the 1300s! Anyway, Du Guesclin rushes to the enemy camp and interrupts a game of chess. He demands a trial by combat, which draws a big audience. And the episode ends in a “feast with the ladies.”

Apparently, knights played a lot of games, based on the frequent mentions of dice, backgammon, and chess in the book. War, too, was a kind of sport. The earliest tournaments were open melee fighting across a large era, barely distinguishable from a battle or a brawl. This was watched by (of course) the ladies at the top of the wall, dressed in the matching colors of their favorite knight.

Related:

The Winter’s Tale and the myth of redemptive technology