Climate change is my family's life now

It's literally the air we breathe

The Book:

Losing Earth: A Recent History

By Nathaniel Rich

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

2019

The Talk:

In the last five years I have experienced climate change. In March 2019, the Elkhorn and Missouri Rivers in Nebraska flooded. The Elkhorn crested five feet above the previous record. Two-thirds of Nebraska counties were in a state of emergency. Fourteen bridges were damaged or destroyed. Two hundred miles of roads were damaged. It was the most expensive disaster in Nebraska history. And the state climatologist said on the news that rapid warm-up events in the spring, like this one, will become more frequent and more intense in the decades to come.

In the last five years I have tasted it. In September 2020, there was a white-brown haze over Omaha that lasted for many days. It was caused by record-breaking wildfires in the Pacific Northwest.

In August 2021, I was swimming with my son at the local pool. All around the horizon, like a ring, the sky was brown. I looked it up afterward. It was record-breaking Canadian wildfires.

In May 2022, the skies in Omaha turned white-brown. This time it was record-breaking wildfires in New Mexico.

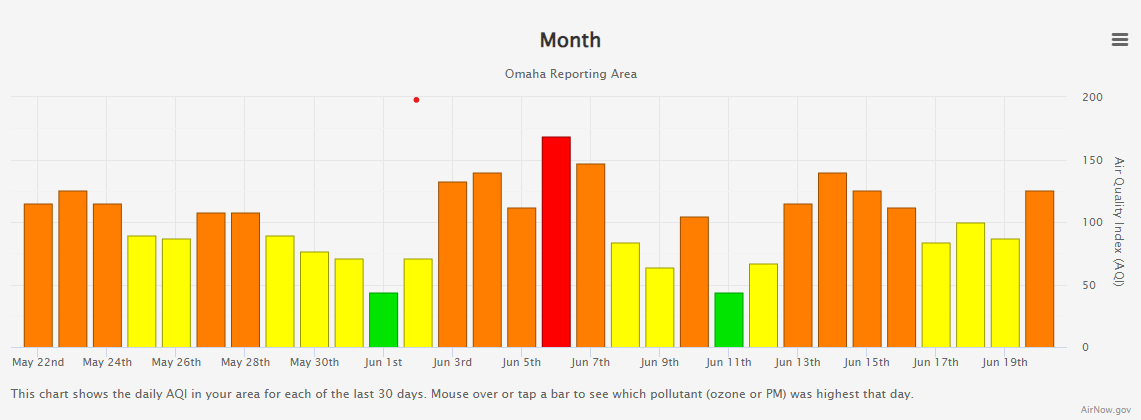

In May of this year, there was a day when my neighborhood was blanketed in a dense white fog with a weird smell. It was the record-breaking Alberta wildfires. The last two months have been hazy, with air quality bouncing between yellow and orange on the AQI index. They say it could last all summer.

When it’s at its worst, you can smell it and taste it on your tongue. It makes your eyes burn, and your throat hoarse, if you stay outside too long.

I have felt it on my skin. Last February, there were so many days in the 60s that I spent the whole day outdoors at the zoo with my son and he went bug catching with the neighborhood kids… in February.

I have walked its streets. When the flood happened in 2019, I could see the Elkhorn River from my childhood home—something nobody had ever experienced before. The bridge by my local Wal-Mart was blown out by the flood as well.

In 2021, a windstorm knocked out power for 190,000 homes in my area. (Over double the last major windstorm in 2017—70,000) Power was out for days for many people, including my coworkers. Trees were shattered in my neighborhood, and clean-up crews with chainsaws piled the refuse up behind my house.

Later that same year, there was flash flooding downtown. The brick street where I’ve gone on dates, met for coffee to network, attended tech conferences, turned into a torrential river. Nobody had seen anything like it before. One phone captured video showing people trapped in an elevator in water up to their necks.

Last year, I went to Naples, Florida, on vacation with my wife. A couple weeks after the trip we were back home on our phones, watching Hurricane Ian destroy the places we had just been. Ian experienced rapid intensification, a common occurrence for hurricanes now due to very warm ocean water.

I have seen it in the faces of my family. In 2020, I was doing dishes and a presidential debate was on TV in the background. They were talking about climate change. My three-year-old son came up to me scared. “I don’t want my house to be on fire.” I turned off the television, and I told him we are safe. But that entire week it was 80 degrees outside. In October.

The next summer we spent a weekend at the lake with my parents. There was a haze over the lake from Canadian wildfires. Never a blue-sky day. My wife had trouble breathing the entire trip, and she used her inhaler multiple times. Seeing her wheezing, I felt so helpless.

As we drove home, we passed by fields of wind turbines. But the smoke was so thick, it was hard to make them out.

All of this was expected. The climate crisis was predicted, peer reviewed, and predicted again several times by the year I was born. It was public record, in the media, and broadly accepted as basic science by government, academic, and industry officials in the early 1980s.

Research was still needed to sharpen the details. But scientists agreed that, barring the cessation of fossil fuels, the warming of the planet due to carbon dioxide would start to have noticeable effects in a couple decades. And these impacts would become increasingly catastrophic in the first half of the 21st Century.

All of this was expected. Until it wasn’t.

When science meets democracy

In his book Losing Earth: A Recent History, Nathaniel Rich chronicles the early years of the climate change issue from 1979 to 1989—the awakening to the issue, the high-stakes meetings and retreats, the promising wins, and the collapse of political will.

It was only after the failure of the first IPCC negotiations in the Netherlands in 1989 that energy companies and politicians organized opposition to climate action through a cluster of lobbying groups and non-profits designed to sow doubt in the science.

But it is unclear to me, after reading this book, that even if you extracted energy industry lobbying and obfuscation, we would’ve reached a quick, effective, long-term global commitment to reducing carbon emissions.

There is this liberal dream that if only you could present the true facts to the public, they would act correctly. If you tell the proletariat they are exploited, the revolution happens spontaneously. This is the Al Gore approach. State the facts clearly, and the will of the people will follow.

In Rich’s telling, the success of “fixing the hole in the ozone” in the 1980s almost makes a mockery of this kind of approach. There was no hole. There was no layer. Levels of ozone declined for two months of the year in an annual cycle around Antarctica, but it wasn’t a permanent “hole.” Yes, CFCs were a serious problem. But the “hole in the ozone layer” phrase captured the media and sent the public into a panic, with animations colorized to dramatize an ever-growing “hole,” like some sci-fi monster’s maw.

In the public, the ozone hole and climate (the greenhouse effect) were conflated together in confusing ways. Many observers thought the climate problem would be solved the same way as the ozone hole. But the “ozone hole” idea was like a meme, a random viral hit, that bypassed scientific literacy and told people to be afraid of going to the beach. It also affected only part of the economy, not everything.

The interface between science and democracy is complicated. The pandemic revealed that if the public sees the scientific process in real time, with “what we know” changing as new discoveries and new data come in, the result is a meltdown of trust.

The history of the communication of climate science, from the 1950s to today, seems eerily similar to the way the pandemic played out. There was a brief moment at the start of the pandemic when the public was panicked enough to follow whatever the best science said. Then the opposition got organized. The doubts, the “independent researchers,” the questions about ulterior motives, the secret agendas, the truthers, etc. But the difference is this: No industry executives or industry-funded lobbyist orgs were required to orchestrate this quagmire of distrust and resistance.

When will it get bad?

But that doesn’t mean the science is wrong.

In 1988, when NASA climate scientist James Hansen spoke before Congress, calling for major action on climate, it was the warmest year ever recorded on Earth.

Rich writes:

Everywhere you looked, something was bursting into flames. Two million acres in Alaska were incinerated, and dozens of major fires scored the West. Yellowstone National Park lost nearly a million acres. Smoke was visible from Chicago, sixteen hundred miles away.

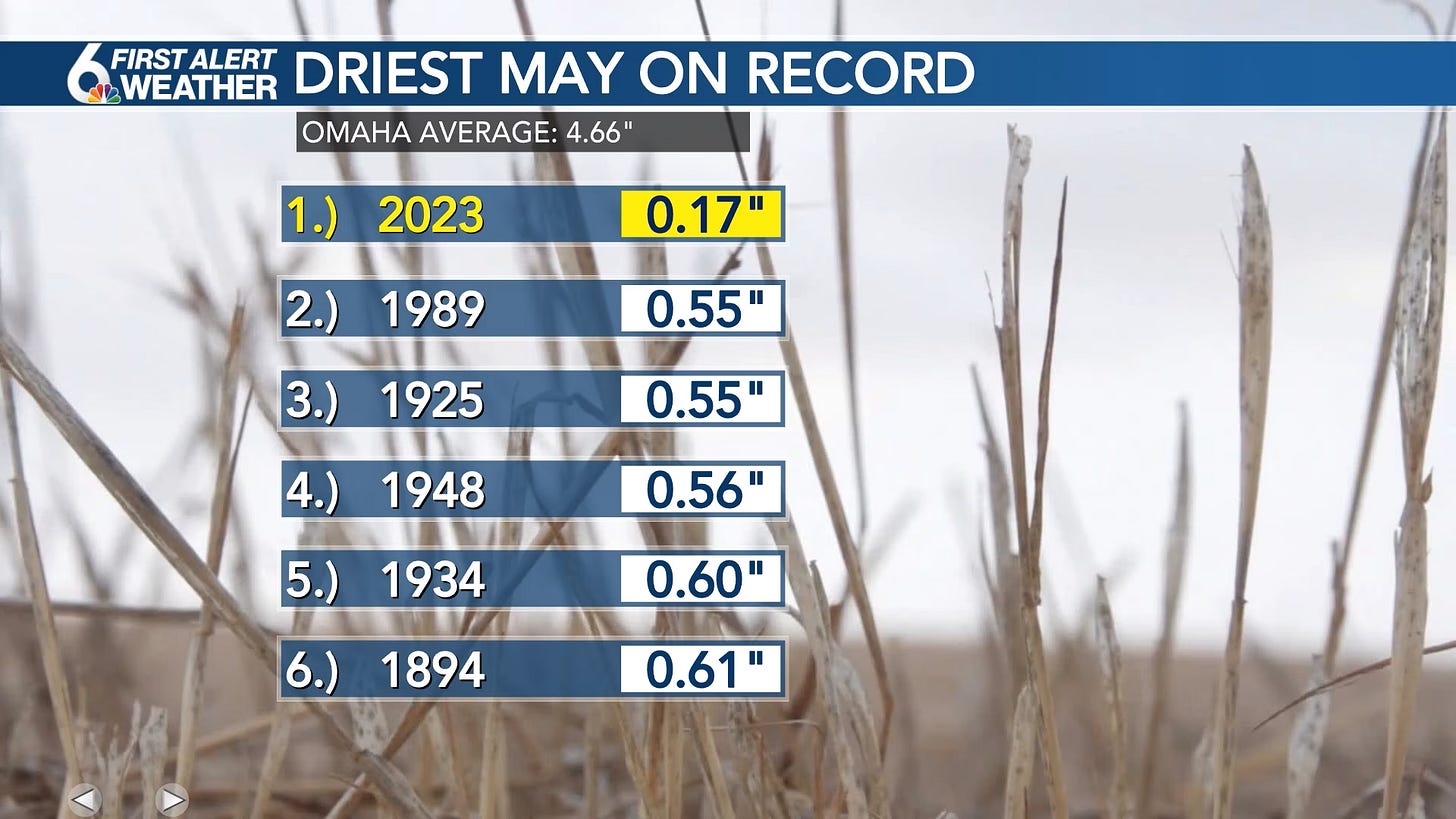

In Nebraska, suffering its worst drought since the Dust Bowl, there were days when every weather station in the state registered temperatures above 100 degrees.

Sound familiar? And yet today 1988 doesn’t even crack the top 10. The top 10 warmest years are:

2016

2020

2019

2015

2017

2022

2021

2018

2014

2010

The year 1988 would be a remarkably cool—shockingly cool—year today. There is no year in the Top 10 earlier than 2010. But 2010 is about to drop out, too: 2023 or 2024 is likely to take the #1 spot.

People want to know when things are going to get bad. Well, I’m just a random person in a not particularly interesting place (from a climate change point of view). But the daily world I walk around in is clearly worse than when I was a child.

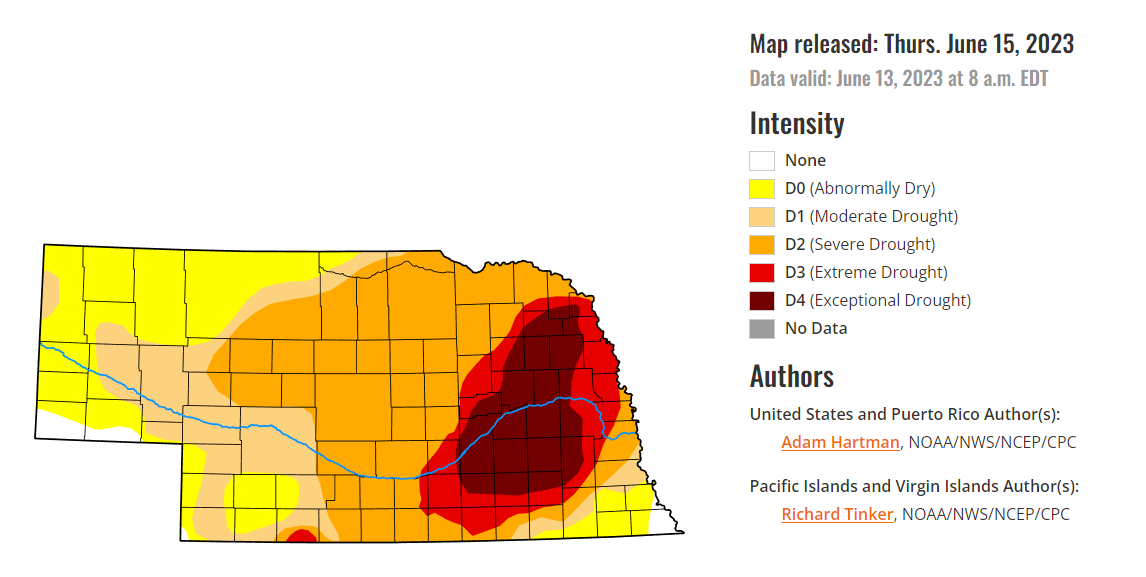

For the past five years, my state has been in drought. Last month was the driest May on record for Omaha, and it wasn’t event close.

Every summer my skies turn white-brown with smoke from wildfires stretching from New Mexico to Canada. The places I inhabit—my old neighborhood, my current neighborhood, my downtown, my favorite summer lake, my favorite vacation spot—have been hit with record-breaking/historic/unprecedented weather events within a five year span. I never thought about air quality before; now it’s a season that lasts half the year.

This is my life now. The next five years will be worse.

Great Lakes states are experiencing smoke pollution this week. Cattle Ranchers in drought are selling off herds. Recurrent flooding causing environmental & economic damage is projected to increase in several regions. Insurance companies are covering more storm damage than ever. Southern KS has received less than 5” of rain in June, normally the wettest month. Last year, rain just didn’t return after Spring. Not enough moisture around to even wind up a small tornado anymore.