Whatever happened to American pragmatism?

We need our Emersonian mojo back

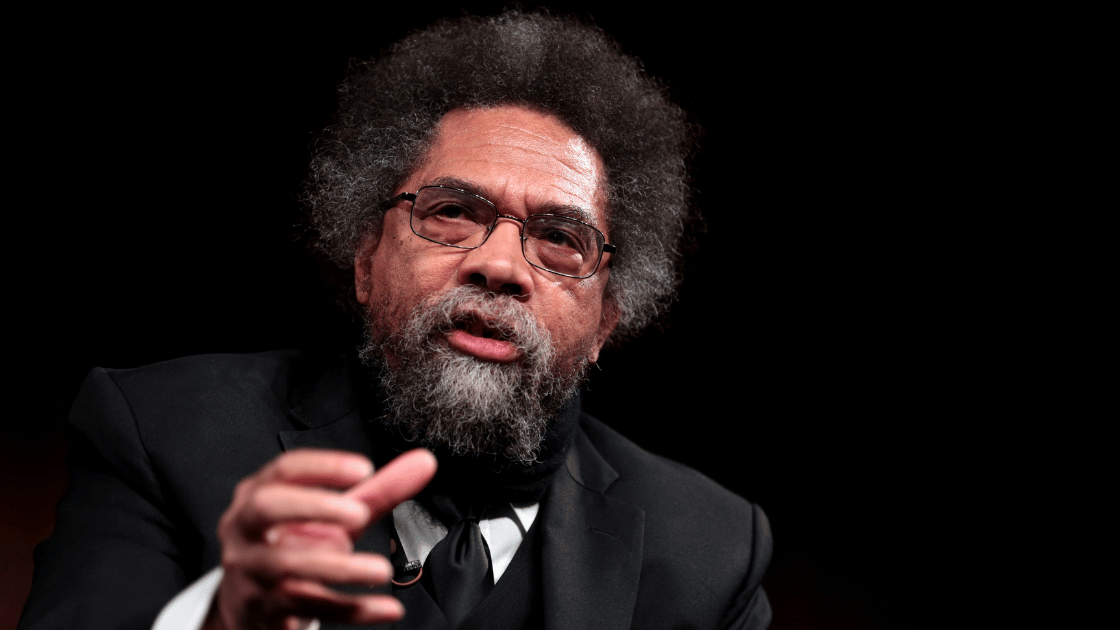

The Book:

The American Evasion of Philosophy: A Genealogy of Pragmatism

By Cornel West

University of Wisconsin Press

1989

The Talk:

In his 1989 book The American Evasion of Philosophy, philosopher Cornel West lays out his personal version of democratic socialism for his Marxist colleagues and fellow activists, a vision which he calls “prophetic pragmatism.” He articulates this by means of an intellectual history of American pragmatism, exploring the ways in which this philosophical tradition has interacted with socialist thought in the American academy. In the beginning he explains that many of his peers on the political left have been confused by his drawing upon pragmatism as a source of inspiration, and this book aims to unpack how he sees pragmatism and Marxism working together.

One of the most interesting parts of the book was the section on Emerson, in which West places Emerson in the larger historical context of thinkers like Marx and Nietzsche. I had not realized before how similar Emerson’s outlook is to Nietzsche, and it made me wonder how many Nietzscheans are unwitting Emersonians. (Nietzsche was a fan of Emerson.) From “The American Scholar”:

“The scholar is that man who must take up into himself all the ability of the time, all the contributions of the past, all the hopes of the future. He must be a university of knowledges. If there be one lesson more than another, which should pierce his ear, it is: The world is nothing, the man is all; in yourself is the law of all nature, and you know not yet how a globule of sap ascends; in yourself slumbers the whole of Reason; it is for you to know all, it is for you to dare all.”

Setting Nietzsche aside, West sees his own democratic socialism as a wedding together of Emersonian libertarianism and Marxist social critique. It is Emersonian in that it values the common man’s potential, experimentation, and flourishing as part of utopian construction (insofar as America is a utopian project). It is Marxist in that it stands in moral judgement of the American system when it crushes “the wretched of the earth,” to use West’s terminology.

West sees in America’s founding idealism a promise, a vision of a future not yet fully enjoyed by many people in America. In one striking section, West gives several rare examples of Emerson limiting his seemingly limitless belief in the power of the individual—and in each case bringing up race as the limiting factor for true genius.

After wondering why England has produced so many geniuses, Emerson wonders:

It is race, is it not? That puts the hundred millions of India under the dominion of a remote island in the north of Europe. Race avails much, if that be true which is alleged, that all Celts love unity of power, and Saxons the representative principle. Race is a controlling influence in the Jew, who for two millenniums, under every climate, has preserved the same character and employments. Race in the Negro is of appalling importance.

It is individual genius which gives man his value, and man’s genius is unbounded—except by his race. Transcendentalism finds its edge there. Even that was a bridge too far for the abolitionist.

In a way, West sees Marx as Emerson’s missing piece, and Emerson as Marx’s missing piece, with each philosophy spurring on the other to greater “provocation,” to use West’s word. Marx points to Emerson’s paeans to freedom and the individual and says, “What about these people?” To Marx’s historical determinism, Emerson says, “Who knows what the future really holds? Let’s free people and see what happens next.”

The evasion of epistemology

West places Emerson as the background out of which pragmatism sprang. This is West’s own contribution, and I think it makes sense. Pragmatism proper, however, as a philosophy, began with scientist and mathematician Charles Sanders Pierce.

One of the key assertions in Pierce’s pragmatism is that ideas (and language) are tools for doing things, not representations of the external world.

This starting point basically throws out modern philosophy from Descartes to Kant, which fixated on our knowing or not knowing the world beyond the mind. The core problem to puzzle over, in modern philosophy, was how thought, language, and ideas within the self represented the outside world.

Pierce sidesteps all of this. (This is the evasion of philosophy in West’s title.) Santayana puts it this way: “Ideas are not mirrors, they are weapons.”

Rather than having to solve knowledge (epistemology) first, pragmatism puts values (axiology) first. “Truth is a species of the good,” writes William James. If ideas are tools, we decide which ideas are true or false based on their usefulness for achieving some end. Ideas are true when they make a difference, get us somewhere, or better yet, get us where we want to go. For example, modern science gains its strength not from theories that are logical, but theories that work.

The trouble for a certain kind of analytic philosopher, however, is that this view opens up a backdoor that he really doesn’t want to open—a backdoor to history, sociology, culture, society, power structures, incentives, etc. Why do we have the philosophies we do? Could it be that they affirm and support certain ways of life? Ways of life that keep certain people in power and keep other people down?

Now you can see where a pragmatic line of thinking has an appeal for the intellectual left, but practically ends the analytical philosopher’s career. (See more on that below)

Furthermore, the view that ideas are primarily tools for doing things shoves the introspective philosopher out into the world. If truth derives from goods, and those goods derive from human life and human communities, then the truth is literally “out there.” It cannot be grasped a priori in the comfort one one’s individual mind; it must be found in the rough and tumble of interaction, conversation, debate, and dialogue. The scientific community (“community of inquiry”) is a helpful analogue for this:

Could LK-99 be a room-temperature superconductor? Community consensus: No.

Is Tabby’s Star surrounded by alien megastructures? Community consensus: No.

Was Oumuamua an alien spaceship? Community consensus: No.

Of course, tools are only useful until they aren’t. When what we want changes, our ideas change. This means the future is open-ended, and thought is never finished. All ideas must be held lightly in the hand because they are subject to change and only helpful for a period of time, much like the scientist’s “working hypothesis” that is discarded when it stops getting results.

As is obvious at this point, modern science is an inspiration and paradigm for Pierce’s pragmatism. But at the same time, it also contextualizes scientific thinking in an important way. (Or, I would say, takes science as a practice and not as dogma) Scientific thinking is helpful to do certain things and has developed to solve certain problems, but it is contiguous with other kinds of thinking. What’s “true” in science is different than what’s “right” in the arts, but science doesn’t trump the arts as somehow more “objective” or “real” or “true.” Science is still a human practice within human communities, and it emerges because of certain things we want, certain values and goals we have. It never stands over the human, rather, it emerges out of the human.

West argues that pragmatism ultimately leads one out of philosophy to cultural criticism, since all our thinking arises out of values, values which emerge out of human practices and communities. We are led to metaphilosophy: We have to examine and interrogate the social ground out of which philosophical thinking emerges.

The rise of Rorty

Pragmatism was later promoted and disseminated to younger intellectuals through the enthusiasm of William James. (Pierce famously distanced himself from James’ interpretation of pragmatism.)

West notes throughout that several prominent pragmatists of the 20th Century—John Dewey, Sidney Hook, C. Wright Mills—also labeled themselves as democratic socialists, only curbing their views in the face of the horrors of Stalinism and Leninism and the rise of the Cold War.

The popularity of Richard Rorty and the Neopragmatists is a secondary cause for West’s book, to give his own context for resurgent interest in pragmatism in the 1980s. However, one rarely hears about pragmatists or neopragmatists today. And West’s take on Rorty may provide some reasons why. West ultimately sees Rorty as a kind of intellectual dead-end (even though Rorty gives him a nice plug on the back cover of the book!).

Rorty’s a professional dead-end, in that, if you take Rorty’s position, there’s no more need for philosophy. But more importantly for West, Rorty’s philosophy is a moral and romantic dead-end. Rorty’s public comments suggest a kind of industrial civilization decadence—there’s no way to defend the Western European way of life, but there’s also no way to criticize it either. According to West, Rorty is content with this final assessment of his philosophy, West is not. There is no open Emersonian future to strive for, and for West, this horizon must always exist.

A future for pragmatism?

I have no opinion about democratic socialism, nor an opinion about Cornel West’s presidential run this cycle. But it’s too bad that there’s not more of a groundswell for the pragmatic ethos in America today.

Richard Rorty died in 2007. Hilary Putnam, another philosopher interested in pragmatism, died in 2016. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy summarized Putnam’s metaphilosophical interest in pragmatism thusly (bold mine):

With the turn of the twenty first century, [Putnam] made ambitious claims for the prospects of a pragmatist epistemology. After surveying the apparent failures of the original enlightenment project, and attributing them to the fact that enlightenment philosophers were unable to overcome the fundamental dichotomies mentioned above, he expresses the hope that the future might contain a ‘pragmatist enlightenment.’ The rich understanding of experience and science offered by pragmatists may show us how to find an objective basis for the evaluation and criticism of institutions and practices. He is particularly struck by the suggestion that pragmatist epistemology, by emphasizing the communal character of inquiry and the need to take account of the experiences and contributions of other inquirers, provides a basis for a defence of democratic values.

What’s the solution to this low-tide of the democratic attitude? And how do we get our Emersonian mojo back? Perhaps such pragmatic enthusiasm requires a few ingredients our cultural moment lacks:

An optimism about the future. West’s history of pragmatism up to the 1980s suggests a growing despair among revolutionaries and idealists, as the modern industrial liberal order became impossible to reform, let alone effectively oppose. West’s 2017 opinion piece “Pity the sad legacy of Barack Obama” surveys a decade of the entrenchment of the established order rather than its reform.

A belief in the power of the individual. Emersonian or Jamesean praise of the individual seems pretty weak in a society where the individual feels so powerless most of the time. We are individualized but not flourishing—getting our personalized playlists, news feeds, and fast food orders, but not starting clubs or organizing meetings. We are stans, not citizens. We demand our right to free speech daily, while our right to assemble shrivels on the vine.

A sense of shared values. In The Revolt of the Masses, José Ortega y Gassett writes, “Not what we were yesterday, but what we are going to be tomorrow, joins us together in the State.” Much of our political will today is spent debating our past, while it is taken for granted that nobody agrees on the future. This is partly a fiction—Americans agree on a lot when they aren’t primed to be ideological. And their actions are often even more pragmatic than their stated opinions. Even so, it’s a widely held belief that Americans are deeply divided and that these divisions are impossible to reconcile.

An unexpected twist

This gets to the fundamental issue raised by pragmatism: If the good precedes truth, then you are at the mercy of your values. If your good is weak, you end up with self-satisfied middle class milquetoast moralism.

For West, the good from which his pragmatism, Marxism, and romanticism flow is Christianity (though his version of Christianity may not be recognizable to many orthodox Christians). This provides the prophetic energy behind his Emersonian and Marxist perspectives, the “provocation” for action and change.

West’s version of Christianity, which he articulates in the final pages of his book, is existentialist, in that he claims no reason for it but a leap of faith, into which he places his total identity and being, while still admitting he “may be deluded.”

To not speak out of a religious tradition, writes West, “one risks not logical inconsistency but actual insanity; the issue is not reason or irrationality but life or death.” (This claim, which is not explained further, suggests that, for West, without his Christian faith, his self would disintegrate. Quite the remark in an academic book.)

Notably, the founder of pragmatism, Charles Pierce, was a Christian too—a devout Episcopalian. In an 1893 essay, “Evolutionary Love,” Pierce rails against the “gospel of greed” prevalent in his time:

As Darwin puts it on his title-page, it is the struggle for existence; and he should added for his motto: every individual for himself, and the devil take the hindmost! Jesus, in his Sermon on the Mount, expressed a different opinion.

In the end, Pierce takes a sentimentalist approach to values and sees sentiments as the proper (logical) ground for moral action. And, in a remarkable twist, if you’ve read all the way to here, Pierce sees his work on pragmatism, logic, science, community, and Christianity, as one singular project. 🤯

So for both West and Pierce, pragmatism is correct but pragmatism isn’t enough. You need some pre-philosophic moral sentiments which come out of a living community.

I end with this extended passage from Pierce’s collected papers that West quotes in his book, which pulls together all the themes I’ve discussed in this essay:

It may seem strange that I should put forward three sentiments, namely interest in an indefinite community, recognition of the possibility of this interest being made supreme, and hope in the unlimited continuance of intellectual activity, as indispensable requirements of logic. Yet, when we consider that logic depends on a mere struggle to escape doubt, which, as it terminates in action, must begin in emotion, and that, furthermore, the only cause of our planting ourselves on reason is that other methods of escaping doubt fail on account of the social impulse, why should we wonder to find social sentiment presupposed in reasoning? As for the other two sentiments which I find necessary, they are so only as supports and accessories of that. It interests me to notice that these three sentiments seem to be pretty much the same as that famous trio of Charity, Faith, and Hope, which, in the estimation of St. Paul, are the finest and greatest of spiritual gifts. Neither Old nor New Testament is a textbook of the logic of science, but the latter is certainly the highest existing authority in regard to the dispositions of heart which a man ought to have.

Related:

12 things this millennial learned about the Reagan Era

Emotions are information: Audre Lorde vs Jonathan Haidt

What if morality is objective but not absolute?

Dr. Cornel West on Socialism | Joe Rogan (YouTube)