Breaking barriers

Encounters with the world’s largest reef

The Book:

The Reef: A Passionate History: The Great Barrier Reef from Captain Cook to Climate Change

By Ian McCalman

Scientific American / Farrar, Straus and Giroux

2013

The Talk:

Australia’s Great Barrier Reef encloses an area of 134,634 square miles, or half the size of Texas. Visible from space, it is the world’s largest reef, and it runs for about 1,400 miles along the coast of Queensland. It is home to the dugong and the large green sea turtle, as well as 400 types of coral, 1,500 species of fish, and 4,000 types of mollusk. A World Heritage Site since 1981, the Great Barrier Reef has existed for hundreds of thousands of years, with some parts going back for millions of years.

In his 2013 book The Reef: A Passionate History historian Ian McCalman tells the stories of men and women who were captured by the reef—emotionally, intellectually, but sometimes physically—and the way their encounter with this remarkable, alien world transformed them.

The culture barrier

African slave traders had a saying about the malarial western coast of Africa:

Beware, beware the Bight of Benin,

Few come out, though many go in

This would be almost more fitting for the barrier reef, which was first encountered as terrifying trap by European explorers. Western sailors had never experienced such a massive region, a nearly impossible maze of shallow coral, jutting up from deep water, that could gut a ship’s hull out of nowhere.

“Here begun all our troubles,” wrote Captain James Cook in retrospect about entering the Reef for the first time. Once inside he and his men were trapped within an “Labyrinth of Shoals” that required perpetual vigilance. Eventually, they discovered narrow gaps within the barrier that could be navigated with care, but for decades afterward reef-caused shipwrecks were a constant along eastern Australia.

But what appeared as a natural barrier was in fact a cultural one—European ship design colliding (literally) with a novel environment. Not surprisingly, the Aboriginal inhabitants of the region did not have shipwrecks, because their outrigger canoes were designed to maximize the extreme tidal changes of the intercoastal area (sometimes varying thirty-two feet or more) for purposes of transportation, hunting, and war.

Throughout the 19th Century, there were high profile cases of reef-wrecked British passengers who were rescued and taken in by Aboriginal clans. Within a few years time, they acculturated to their new community and new life. (One became a master canoe builder.) Sadly, when these people returned to British society, they were psychologically wrecked by the second culture shock, unable to re-enter their old life ever again. Most were severely depressed or died shortly afterward. They had crossed the cultural barrier once successfully, but crossing it a second time was simply too much.

The imagination barrier

One of the interesting evolutions in the book is the way public perceptions of the reef changed as technology developed. Although there were coral samples sent back to England and Europe in the earliest decades of discovery, the beauty of the reef could only be expressed through drawings and written descriptions. British illustrator Harden Sidney Melville journaled in 1843:

There were fields of divers kinds of marine vegetation of many colours, some having the appearance of a plateau of variegated penwipers with fancy fringes; corals and corallines branching out into noble terraces, with tints of rose and violet-blue; acres of orange-red brain-stone glittering in the sun, and lying in beds of green sea moss; clamp shells (the Calme giga) gaping open with the fish spread out like a velvet cushion, and spotted like a leopard; starfish blue and starfish grey, lying in sandy beds; dogfish and tiger sharks darting about in the channels; crabs and crawfish; and millions of things of life, seen and unseen.

Having seen pictures, it’s easy for us to recognize what he was trying to describe in words. However, when William Saville-Kent published his magnum opus on the reef, The Great Barrier Reef of Australia: Its Products and Potentialities, in an extra-large format book with hand-colored illustrations in 1893, it was revelation.

Early black-and-white photography finally allowed for pictures, followed by experimental underwater photography. In addition, new technology for getting into the water itself developed. The descriptions of 1920s diving helmets feel particularly harrowing:

Made of galvanized iron and with two glass windows, its air supply depended on continual hand pumping.

Later in the 20th Century, the development of scuba diving and underwater documentary filmmaking became a key tool for environmentalists looking to change public consciousness and make an aesthetic appeal for the reef’s protection.

Today you can experience the Great Barrier Reef in Google Street View, in virtual reality, or watch countless 4K resolution videos on YouTube:

The species barrier

One of the interesting ideas in the book that I hadn’t heard of was “reticulate evolution.”

Australian scientist John Veron, the world’s leading expert on coral reefs who has spent over 7,000 hours scuba diving in reefs, noticed from his experiences studying coral all across the world that there were the coral from the same species that looked quite different, and different species that looked almost indistinguishable from one another. Something really weird was going on, and the historic taxonomy of corals that he had learned didn’t make any sense.

His proposal that was that coral (which are animals) may, in fact, evolve in a more “plant like” way, called reticulate evolution. It goes something like this: The textbook picture of evolution is of a branching tree, each species separating out from the others, and then either separating further or going extinct. However, based on advances in genetic science, some plant geneticists have argued that in the plant world the genetic boundaries between species are not so cut and dry. Genetic material is shared and spread across species in a “netlike skein of evolutionary threads.”

The proposal is a revolutionary one, especially because modern biology is founded on taxonomy, literally the origin of species. If evolution moves between or, in a way, without regard to species, then our whole conception of nature, evolution, and life may need to change too. In other words, where we once saw species as barriers, there may (in some cases) be none.

The climate barrier

Veron is also known for sounding the alarm on the destruction of the reef around the world. In 2009 he gave a speech at the Royal Society entitled, “Is The Great Barrier Reef on Death Row?”

There are several active forces destroying the reef. But two are perhaps the biggest ones. The first is coral bleaching, which occurs during underwater “heat waves.”

Coral is dependent on the algae that live on and inside of it. When water warms, the algae produce too much oxygen, and it threatens the life of the coral. The coral expels the algae in order to save itself, as a kind of last ditch attempt, like a kind of shock.

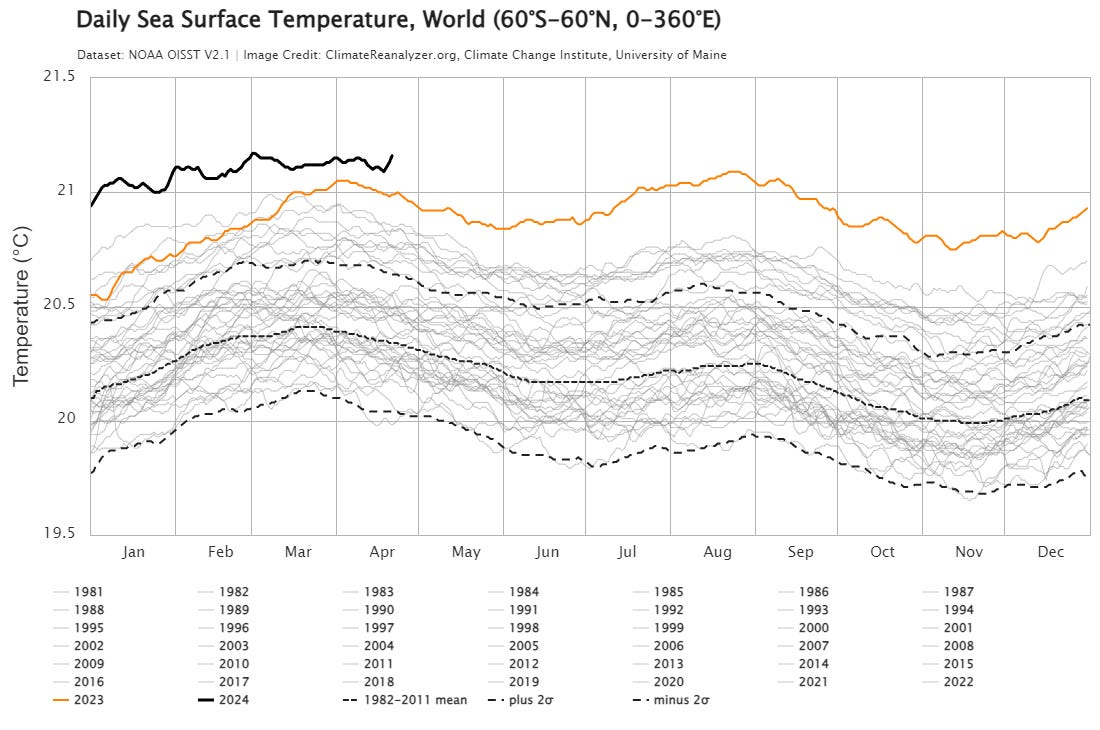

There have been five severe coral bleaching events on the Great Barrier Reef since the publication of this book a decade ago: 2016, 2017, 2020, 2021, 2022. As I write this in April 2024, the reef is experiencing the most severe heat stress on record within the context of a global mass bleaching event stretching from the Red Sea to the Caribbean. While coral can recover from these events, it is a sign of extreme stress.

The second threat is ocean acidification, which is caused from carbon dioxide in the atmosphere being absorbed into the ocean. Acidification eats away at the coral, dissolving it into dust. McCalman describes a likely near-future in which the underwater coral towers of the barrier reef weaken to the point that major storms (which have been increasing in intensity) shatter the reef into pieces.

Already, in the last quarter century, half the Great Barrier Reef has been lost. And the scientific view is that the Great Barrier Reef could be gone by 2050, not simply broken but dissolved. And the entire lagoon-like ecosystem (the size of Nebraska and Iowa combined) that this barrier protected from the ocean will be gone as well.

Although there are attempts to save the reef from destruction, the biggest problem seems to be that there is no protection, no wall, one can put around it. If oceans heat up, the reef will bleach. If the carbon-rich atmosphere acidifies the oceans, the corals will dissolve. The future of the world is the future of the reef. There is no barrier.

Related:

Climate change is my family's life now

Burning down the memory palace

Aerial video shows mass coral bleaching on Great Barrier Reef amid global heat stress event (Guardian)

Reef Monitoring Dashboard (Australian Institute of Marine Science)