Do we cover our chains in flowers?

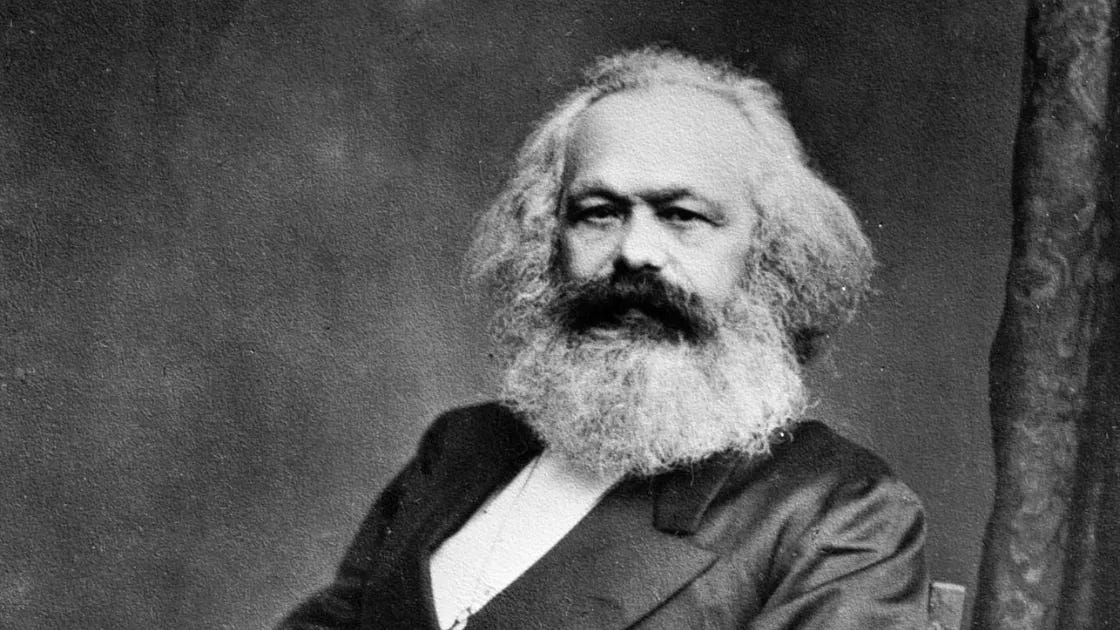

Marx, me, and the bourgeoise

The Book:

Karl Marx: Thoroughly Revised Fifth Edition

By Isaiah Berlin

Princeton University Press

2013 (First published in 1939)

The Talk:

In his 1939 biography Karl Marx: His Life and Environment Oxford historian of ideas Isaiah Berlin charts the intellectual trajectory of one of the most influential thinkers of the modern industrial age. Along the way he (rather politely) identifies the contradictions, inconsistencies, mistakes, and wrong predictions of Marx, while also explaining why Marx became the 900-pound-gorilla that all revolutionaries, reformers, and critics of modern industrial society have had to relate to since his death.

There are few Freudians now, but talk therapy and the belief that your adult problems go back to your relationship with your parents is ubiquitous1. In the same way, even though Marx and marxism are broadly anathema to the American public, his criticisms of capitalism remain culturally resonant.

To wit, Dave Ramsey.

Ramsey’s chains

Dave Ramsey is a conservative Christian radio talk show host who gives financial advice. His program—Financial Peace University—helps people get out of debt and build wealth. (His zero-debt stance, if taken strictly, means buying your cars and house with cash.) He regularly jokes about how terrible the government is and is very proud of being a small business owner. All this to say, he’s no Marxist.

But one of the Bible verses that he quotes, that he builds his whole curriculum on, that may be considered the cornerstone of his whole message is Proverbs 22:7: “The rich rule over the poor, and the borrower is slave to the lender.”

Ramsey takes this slavery imagery far. In his speeches he walks across stage with a heavy chain to illustrate financial bondage. He talks about the many ways that society is designed to trick and trap people into debt. He wants you to get mad. He wants you to get angry. He wants you to get fired up. You can beat this evil system, he preaches, you can escape and be liberated.

Ramsey describes this in terms of Biblical principles but his advice accords pretty well with most financial self-help books and the kind of financial advice you find online. The only way to be truly free is “passive income”—i.e., capital. Rental properties, commercial real estate, investing in stocks, etc. Own things that people pay you for without you having to do labor. Then you will achieve freedom, peace, joy, wellbeing, and relief from sorrow, anxiety, and strife. Salvation.

Karl Marx says: Capitalism is an oppressive economic system in which the rich possess all the capital and rule over the working class. And the only way for the working class to be free is to take the capital for themselves. Once workers have society’s capital, they will no longer be oppressed.

And the capitalists are like: Yep. No notes. You have nothing to lose but your chains.

The salvation that Ramsey et al offer is purely individual. By taking personal responsibility and paying all your creditors, you can get for yourself a little capital of your own, your own little taste of the ruling class.

The middle class dream is freedom from labor through the acquisition of capital. If the current system was destroyed, of course, you wouldn’t be able to experience that freedom. You need the system to keep going—the system we all agree is bad—so that you personally can be saved.

In addition, the middle class dream necessarily means that not everyone can do it. If everyone in America owned rental properties, who would we rent them to? Middle class freedom needs an underclass to be realized.

Marley’s chains

One of the media narratives to develop out of the recent presidential election is that Democrats have “lost” the working class, and Republicans are “now” the party of the working class. This is mostly a matter of vibes. At least as of May 2024, 31% of Republicans self-identify as “working class” compared to 28% of Democrats. A difference, but not huge.

But this is another way in which we all take for granted the idea of the working class as a well-defined constituency that any American political party needs for legitimacy. To be “working class” is to be more real, more authentic, more American—even more masculine.

Because I have a college degree, I am apparently not “working class.” But immigrants are not working class, either. The “American working class” are not the people processing food in plants, serving in restaurants, building houses, cleaning houses, providing elderly care, or harvesting food. Or the people in other countries, like virtual assistants in the Philippines or factory workers filling our fast fashion orders in China. Those, too, are not “the American working class.”

The American working class seems to be just the lower middle class. All this hubbub is really subclasses of the middle class fighting themselves and debating what should be done to the people below them2.

It is those people—those who live in much more precarious economic and legal situations than the “American working class”—that are the most analogous to Marx’s proletariat. They have “nothing to lose,” thinks Marx, and so their self-interest is ultimately the destruction of both the ruling class and the bourgeoise.

Why the bourgeoise? Because, Marx argues, it’s the middle class that makes the proletariat. The Victorian middle class household had servants to cook, clean, run errands, drive their carriage, sew their clothes, etc. Today (after 180 years of automation) we have externalized these servants into fast food workers, housekeepers, Uber drivers, and sweatshop workers. To be, literally, middle class, is to have people to do the things we need to live comfortably (i.e. “essential” workers).

My sympathies, however, would send Marx into an apoplectic rage. To him the sentimentalism of the middle class is a kind of rear guard action. The middle class gives the illusion of care for the poor when the topic is salient, but their true interests lie in the status quo and will always revert back. Marx’s bitterest bile is reserved for the middle class socialists3 of his era, who speak in revolutionary platitudes, garner big crowds, but won’t burn down the system.

As I was reading this book, I kept thinking of Charles Dickens, who was walking the streets of London at the same time as Marx.

“But you were always a good man of business, Jacob,” faltered Scrooge, who now began to apply this to himself.

“Business!” cried the Ghost, wringing its hands again. “Mankind was my business. The common welfare was my business; charity, mercy, forbearance, and benevolence, were, all, my business. The dealings of my trade were but a drop of water in the comprehensive ocean of my business!”

It held up its chain at arm’s length, as if that were the cause of all its unavailing grief, and flung it heavily upon the ground again.

In Dickens’ Christmas Carol, the ghost of Jacob Marley is wrapped in chains, forged by his cruelty during life. The salvation of Scrooge is that of a changed heart—from miserliness to benevolence, from coldness to warmth toward his fellow man.

Like in the case of Dave Ramsey, Scrooge’s salvation is personal; the system goes unquestioned. The whole “revolution” occurs at the level of private sentiments, while the social structures that produce Scrooges keep on producing Scrooges. Berlin writes, describing Marx’s point of view:

Most individuals concealed their own dependence on their environment and situation, particularly on their class affiliation, so effectively, even from themselves, that they quite sincerely believed that a change of heart would result in a radically different mode of life.

The middle class taboo against violence

For Marx, society is war—and not an emotional one. Capitalism is violence against the proletariat, and it must be repaid in no other coin but violence.

Berlin makes it clear that Karl Marx pushed for catastrophic national and worldwide violence on a mass scale. Marx sees violence as more real than thoughts. History matters, feelings do not. And history is defined by major events of extreme violence. Violence is material. Violence is, in a way, empirical.

For the middle class, however, violence is taboo. “Violence has no place in America.” We will do whatever it takes to move violence to the perimeter, to the periphery of our environment. It’s white collar crime, not violent crime. It’s violent crime but it’s not in my part of the city. I can’t imagine committing violence myself, and the institutions that surround me ensure there will be no violence. (This is their purpose?) The result is a society in which the possible overthrow of the system is constantly and firmly suppressed.

“Can’t we all just get along?” is the cry of the middle class man4. It’s the cruelty we don’t like. We accept the system, if only people (or laws or policies) weren’t so mean sometimes. The middle class liberal wants to adjust the thermostat to make things more comfortable for everyone. Maybe they want to adjust it further than others, but violence is unacceptable.

I’m the bad guy

Berlin writes, summarizing Marx:

[Political, social, religious and legal institutions] employ…a whole army of ideologists: propagandists, interpreters and apologists who defend the capitalist system, embellish it, and create literary and artistic monuments to it, likely to increase the confidence and optimism of those who benefit under it, and make it appear more palatable to its victims — in Rousseau’s phrase, ‘cover their chains in garlands of flowers’.

Marx appeals to me when he talks about the conditions of the working poor in his day. Like some kind of 19th Century Christian socialist poet or Chartist, I’m morally outraged. When I read the works of Marxists, I resonate with their attacks on cruelty, on dehumanization, on alienation. I cannot abide those public figures who are mean and unfeeling toward their fellow man.

But Marx’s view is that, in my criticisms of the status quo, I’m the enemy. I’m the one upholding the illusion of peace—covering our chains with garland—while the cruel ones, the cynical ones, see society much more like Marx, like society as war. My insistence that it’s not a war, that the solution is for more people to be kind and respectful to one another, only ends up serving the oppressor, or rather, the oppressor-generation machine that is the current social order. My support for non-violence ensures violence.

In short, I’m the bad guy. And yet Marx would not blame me personally for my own values. I’m simply playing out my class incentives perfectly. Everyone does. Marx doesn’t want me for his revolution.

Related:

Emotions are information: Audre Lorde vs Jonathan Haidt

Whatever happened to American pragmatism?

Climate crisis on track to destroy capitalism, warns top insurer (Guardian, 4/3/25)5

Even if this is likely not true. See The Nurture Assumption.

Berlin writes, describing Marx’s view: “The structure of the modern state reflects the domination of the bourgeoise - it is in effect a committee for managing the affairs of the bourgeois class as a whole.”

One big takeaway I had from this book was the remarkable variety of socialists and socialisms in the 19th Century. Marx was one stream in a river delta of radical social thought. Today we equate socialism and Marx, but nobody in Marx’s lifetime would’ve done so.

I keep coming back to Ke Huy Quan’s speech in Everything Everywhere All At Once as the quintessence of middle class morality: “Please! Please! Can we just stop fighting? I know you are all fighting because you are scared and confused. I'm confused too. All day, I don't know what the heck is going on. But somehow, this feels like it's all my fault. The only thing I do know is that we have to be kind. Please, be kind, especially when we don't know what's going on.” (Rodney King: “Can’t we all just get along?”)

“The world is fast approaching temperature levels where insurers will no longer be able to offer cover for many climate risks, said Günther Thallinger, on the board of Allianz SE, one of the world’s biggest insurance companies. He said that without insurance, which is already being pulled in some places, many other financial services become unviable, from mortgages to investments.”