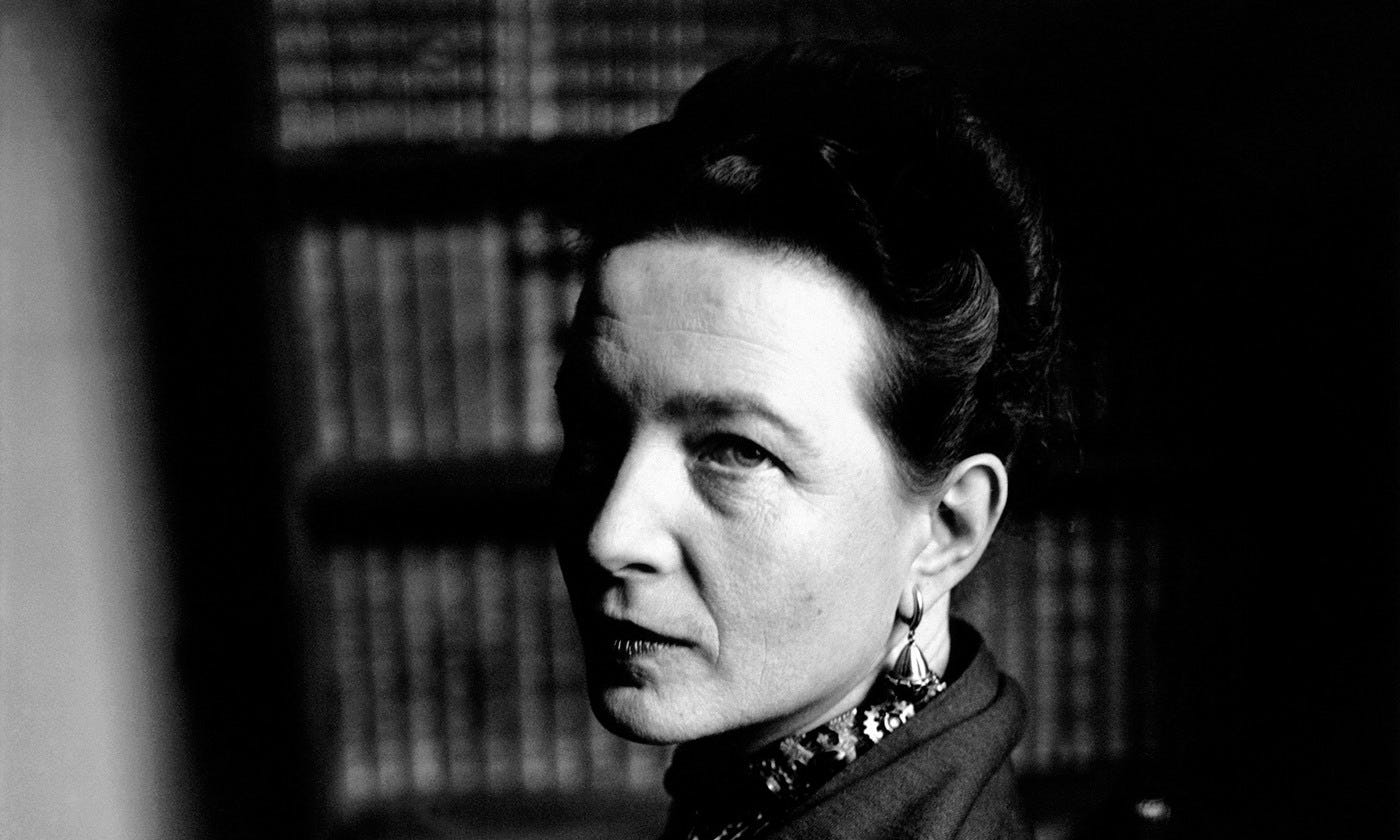

Simone de Beauvoir: We have a moral duty to live our freedom

And fight that others may have theirs

The Book:

The Ethics of Ambiguity

By Simone de Beauvoir

Translated by Bernard Fretchtman

Open Road

1947

The Talk:

In her 1947 book The Ethics of Ambiguity French philosopher Simone de Beauvoir sets out to defend existentialism against the claims that it is amoral and egocentric.

Existentialism begins with the brute fact of our own existence. We exist.

Descartes grounded his philosophy by trying to find the only belief he couldn’t possibly doubt. He cannot doubt that he exists; therefore, one’s existence becomes the starting point for thinking about everything else. Beauvoir roots her existentialist philosophy here.

This line of thinking places the subjective before the objective; my own subjective experience of myself is the thing of which I’m most sure, while the objective, external, physical, concrete world is less firm.

Some believe that philosophy took a wrong turn with Descartes, as this dualism, this divide between the subjective and the objective has caused a lot of paradoxes, tensions, and contradictions—the “ambiguities” of Beauvoir’s title—as I’ve examined before in discussing Kant, Schopenhauer, and Nagel. (Even Robert Frost wrestles with this tension of the inner and the outer!) The self-knowing individual confronts an external, concrete world that is not like itself but at the same time cannot be escaped.

From Existentialism to Oprah

While this may seem like a rather abstract and academic discussion, it is often the background assumption that we wrestle with in many cultural debates. When popular spiritual gurus say, “We are spiritual beings having a human experience”—that’s it. That’s the articulation of the gap of my subjective mental experience (which feels expansive and limitless, even deathless) and the “facticity,” as Beauvoir calls it, of the material world: the parents I was born to, the body I inhabit, the historical era I must pass through, my inevitable mortality.

These are not only spiritual perspectives, they are political ones as well. I am a man, white, and American. But it’s also true that I happen to be a man, white, and American. I could have been otherwise. I could have a different body, a different family, a different country. But I cannot be non-thinking, non-subjective and still be me. So there’s some kind of “me” that (at least conceptually) exists independent of my personal history1.

John Rawls has a famous thought experiment in which we attempt to design the most just society by imagining what rules we would create if we had no idea who we would be born as. We imagine ourselves deliberating behind a “veil of ignorance,” after which we might be born into a poor family or a rich family, for instance. If very few people are rich, then our chances of being rich would be very slim. So ideally, we would make society a place where you would be unlikely to be poor, and even if you happen to be poor, it would be with as little misery as we could make it—because that could end up being you!

What is relevant to our discussion here is the liberal moral imagining of people without their externalities (sex, gender, race, class, etc.) and the idea that justice is tied to treating people as beings who, on some level, transcend their material.

Thinking beyond justice to human flourishing more broadly, John Stuart Mill articulates a similar vision in which he places the flourishing of the human individual at the center of his 19th Century utilitarianism project. Individuals should be free to pursue their own subjective dreams, their personal goals, because those pursuits often inspire and benefit many others, thus raising the overall happiness of everyone. Accidental facts—objective facts that just happen to be, like being born female—shouldn’t limit human freedom to grow in an open-ended and non-determined way (the only limit being the harm of other individuals). Subjectivity over objectivity.

These ideas have made some people very upset. There is a direct line between Simone de Beauvoir’s most famous quote, “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman,” and someone like Matt Walsh creating his What Is A Woman? documentary.

The conservative’s argument is that liberalism is a rejection of objective reality, while liberalism sees itself as bearing witness to a transcendent moral reality which places the subject at its center.

Which brings us back to Beauvoir’s Ethics of Ambiguity.

To act freely in our freedom

Here’s my go at explaining Beauvoir’s existentialism: For Beauvoir, we find ourselves existing. And, at least as far as subjective experience is concerned, we experience ourselves as free. Freedom to act necessarily points to the future. We are beings that lean toward the future, so to speak, a future that is open, unknown, undefined. What makes that future into something, and not just possibility, is our action. We must act first, and our actions create our ends.

In other words, we are beings who act the meaning of our actions into reality. As individuals, we make our own meaning in life, a meaning that is out in front of us, in the future, which we act toward, even if we fail to reach it.

It is desire which creates the desirable, and the project which sets up the end. It is human existence which makes values spring up in the world on the basis of which it will be able to judge the enterprise in which it will be engaged.

In fact, as long as we are acting toward the future, we never fully reach our meaning, even though the future never stops being the source of meaning in our lives.

An additional challenge is that we can only act in the objective world, the world of bodies and time and space and people and institutions. Acting in this world, we are limited and bounded. The specific situation in which we find ourselves is the content through which our freedom expresses itself.

In a similar way to how Kant sees rational beings as duty-bound to obey reason, Beauvoir argues that we have a moral duty as free beings to act freely. We are free, but we also have a duty to act as free. The great temptation is to refuse our own freedom, and we do many things—like give ourselves over to ideologies or principles or social norms—in order to defer our freedom onto someone or something else.

To act free is the purpose of our lives, though what exactly we are acting toward cannot be decided a priori. It can only happen in the living. Although happiness is sometimes a consequence of free action, it is not always so, and freedom is more important than happiness. Kant says, “Our existence has a different and nobler end than happiness,” and I believe that Beauvoir would agree, though she would place freedom in place of rationality.

In a way similar to Kant and Mill, Beauvoir sees the only moral limit to individual freedom as the restriction of others’ freedom. My freedom can’t be allowed to limit the freedom of others. We should will the freedom of all free beings. (In this way, she has a “Kingdom of Ends”-style moral universe in mind.) At the same time, we must oppose those whose actions threaten the freedom of others (i.e. kill Nazis).

Existentialism as war-time ethics

Beauvoir writes her book in the years immediately following World War II. Although her ideas align broadly with modern liberal beliefs about individual freedom, there’s a definite edge to her thinking that made me think she had the war in the back of her mind. Everyone she was writing to in France had experienced the war. Easy or pat answers to moral dilemmas would not satisfy.

If we think about the ethics of war time, of occupation, of resistance, Beauvoir’s ideas hit different:

The individual has a duty to act and to assert their freedom.

They find themselves in a situation they did not choose.

But it’s up to the individual to decide what the situation they find themselves is going to mean.

Even if we lack power, we still have will—perhaps the only thing we have in dire circumstances.

The temptation is to look away, to stuff one’s head with some easy propaganda, rather than see one’s self as an actor, an agent, with a role to play, even if what that means exactly is completely undefined.

You may act toward a goal that you might never achieve, yet it is right and moral for you to do so.

Victory is not built into the arc of history or the fabric of the universe. Failure and defeat are live possibilities.

You may take enormous chances, perhaps in your ordinary personal daily behavior, that may only have a dubious effect on the outcome of, say, defeating the Axis. Yet you should.

We act not for the present but for the future—undefined, unknown, unclear, uncertain.

For Beauvoir, there are no moral rules or principles. Every concrete situation has its own specific details, its own ambiguities. We must act morally in ambiguity (another meaning of the Ethics of Ambiguity) by taking full responsibility for our actions rather than pushing the responsibility of our actions onto someone else. (Think Nuremberg Trials)

In a twist on the idea that “if there is no God, everything is permissible,” Beauvoir claims that “if God does not exist, man’s faults are inexpiable”—we are fully responsible for what do. To survivors of World War II, that probably seemed like both a terrible burden and an unavoidable truth. The heroes of the war committed acts of enormous violence, death, and destruction. They did it for good reasons, but they still had to bear the responsibility for what they had done.

Existentialism as adulting

The characteristic feature of all ethics is to consider human life as a game that can be won or lost and to teach man the means of winning.

Ethical systems can be grouped by what they place as their chief value—their summa bonum (ultimate good):

The classical view places happiness (or wellbeing) as the ultimate goal.

Kantian ethics places duty to reason at the top, over and against happiness.

For Beauvoir, freedom is absolute, beyond rational principles and beyond happiness in some cases. (Better to die free than happy)

Freedom as an ordering principle for morality may seem at first glance counter-intuitive. How can doing what you prefer or pursing one’s self be an ethic? Doesn’t morality tell us what we can’t do, musn’t do? Isn’t morality a limiter of behavior rather than a validator of behavior?

This is where we get to the great divide. For the traditional moralist, this is straight up amorality, egotism with a gloss of high-minded justification, a free pass to libertinism. (Beauvoir’s own open marriage, polyamory, bisexuality, nude photography, feminism, defense of abortion, etc. only confirm everything they suspected.)

But Beauvoir might argue that in the concrete situation before her and her readers, the occupation of France followed by the rising threat of Stalinism, the moral question at hand is if fundamentally free individuals will live free or not. In that context, to live in one’s freedom is an act of resistance, a political and moral action.

Leaving the future open, for one’s self and others—even if one cannot define what it is or what it ought to contain—is a matter of vital importance. Obeying in advance, deciding to not act freely, is the easiest path to follow, the great temptation. Surrendering one’s freedom is to let the enemy win; that’s the path to ruin, for us and those around us.

Rather than being an abdication of responsibility, argues Beauvoir, to live freely by not limiting one’s choices to any a priori moral principles or policies or positions is to grow up. It is to take every situation as it really is, in its specificity, concreteness, murkiness, and ambiguity2.

In short, existentialism is a call to become an adult in a world that wants to treat us as children, where it is very easy to live as children. We may or may not have power, but we have a duty to live free and to live for the freedom of others. Bravery required.

Related:

Picasso! How Europe's avant-garde won over Americans

Joan Didion: Voice of the Silent Generation

Cf. Avicenna’s Floating Man thought experiment

Another great essay about a philosopher about whom I knew very little. The bullet points near the end remind me of another book written after WWII: Viktor Frankl's Man's Search for Meaning.

Excellent stuff, it’s hard to explain philosophy so clearly!