Does anything really matter?

The modern search for values

The Book:

The Women Are Up to Something: How Elizabeth Anscombe, Philippa Foot, Mary Midgley, and Iris Murdoch Revolutionized Ethics

By Benjamin J. B. Lipscomb

Oxford University Press

2022

The Talk:

All therapists and online self-help articles agree: If you want to live a happy life, you must live according to your values.

But which values should one have? Well, that’s up to you. Which values would you like to have? Nobody can answer that for you. That’s where the therapy ends, and you’ve got to look inside yourself, and just go for it.

This advice works because most people are going to pick the same things. Like when you ask people to think of a random number between one and ten, and they usually say seven.

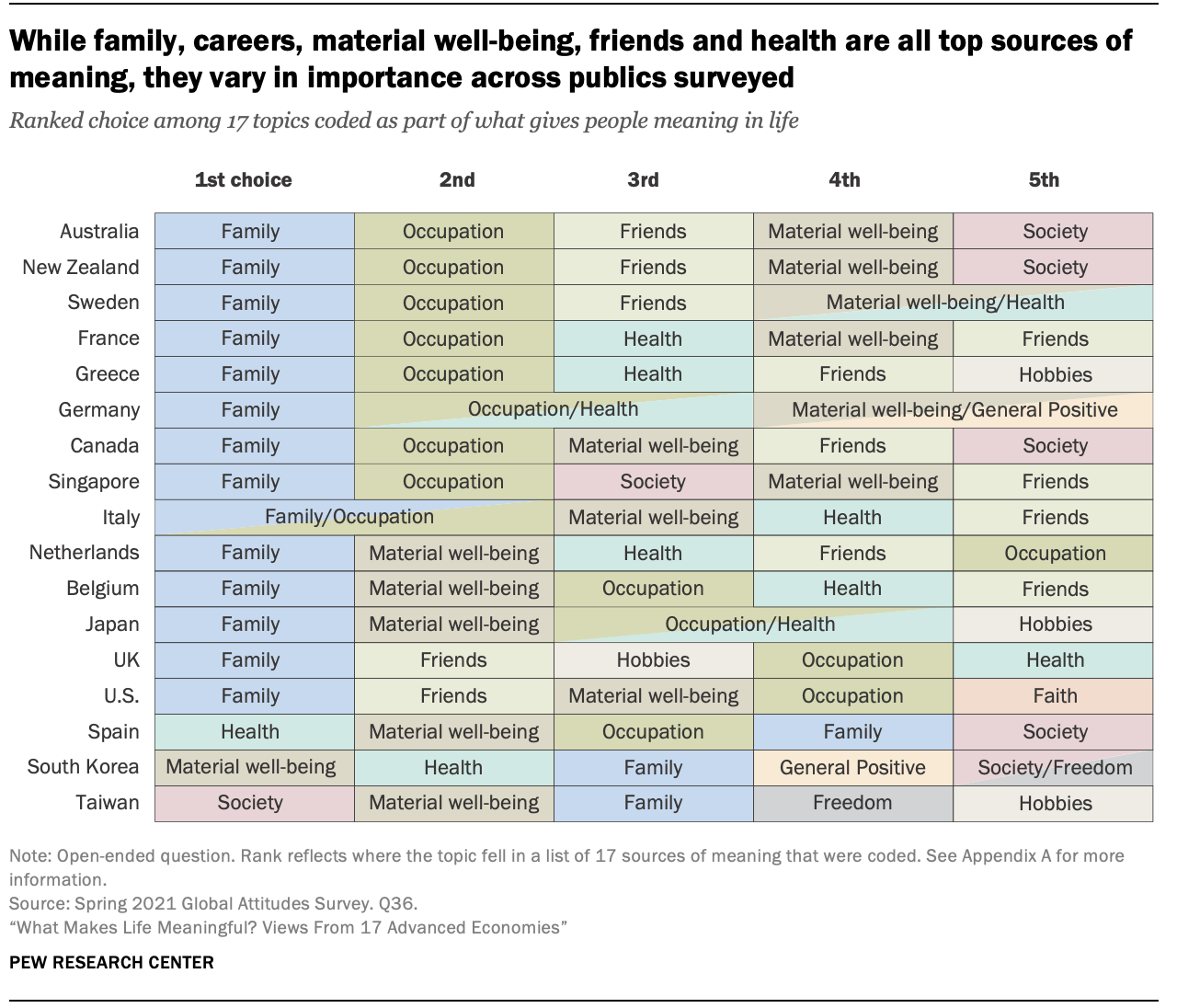

Either because of some biologically-based human universal, or because we were socialized at rough the same place and time, or because we each imperfectly perceive the Absolute, we generally agree on the same values. When you survey people, you find that people want roughly the same things out of life.

As Aristotle writes in his Rhetoric, “Human beings are naturally adequate as regards the truth and in most cases hit upon it.” We *say* it’s up to the individual to decide their own values, but we can only say that because it’s certainly not.

We all collectively agree that this therapeutic advice doesn’t apply to people on the far ends of the bell curve: Serial killers may live in alignment with their values, but we don’t mean that. They may build their life around experiences rather than possessions, but that isn’t what we meant. We meant climbing Machu Picchu or something like that.

Make a life that’s meaningful to you. The range of acceptability is implied.

Forced choices

But this modern idea—that values are basically just personal preferences that gain importance by squeezing them—remains a powerful one. It remains powerful because, like dieting, it works half the time. Every diet makes you conscientious about your eating, regardless of the particulars. So every diet is going to work somewhat. Spending time reflecting on what one values most, and orienting one’s life around it, will surely make one happier—at least half the time, at least for a while.

The myth also works for three other reasons:

1) We live in a society with an enormous amount of choice.

2) We live in a pluralistic society.

3) We don’t like anyone telling us what to do.

We live in a society where we are constantly put the question: “Well, what would you like to do?”

What clothes would you like to wear?

What foods would you like to eat?

What shows would you like to watch?

What activities do you want to do?

Where would you like to go to college?

What would you like to major in?

Who would you like to date?

Who would you like to marry?

Do you even want to marry?

Where do you want to live?

Do you want to have children? If so, how many?

What do you want to name your kids?

This open field of choice would be utterly baffling to most humans who have lived. And yet it is the work of our lives. What’s more, most of the time we don’t really know the answers. We pick something randomly, arbitrarily. Or we just do what people around us do. Or we just look inside of ourselves, grab whatever we find there, and just… go for it.

In addition, every day we bustle around and brush up against people with different opinions. But most of us just want to get through a day without hassles. Each person we meet has a complicated life story, stories we are completely unaware of. Live and let live. To each his own. Don’t go looking for trouble. We’ve all got to get along, even though we’re never going to be on the same page. You do your thing; I’ll do mine. Let’s agree to disagree.

And finally, it sometimes feels like to choose values (or to express them out loud) is to put an obligation on someone else. And we are a society that kicks against any kind of obligation. (We call this freedom.) The only permissible kind of obligation is the choosing to be ruled by something or someone else, which always feel a bit like a game. I mean, you could choose to live according to the magisterium today… or you could, just, not.

Values choose you

We hold these truths to be self-evident because they are helpful. But while this modern myth makes sense of some parts of our existence, it makes no sense of others.

We are not just particles. We are waves.

That is to say, we are not merely atomized, individualized agents, willing choices out of nothing. We are oceanic beings.

I apply my best critical thinking to vote for president, and I end up voting right along with my age, income level, education level.

I see protests and riots across the country against racial injustice, and I feel a prick of conscience, that I must do something to make a difference.

Nearly all my friends who grew up religious like me have become either less religious or non-religious. Each has their own unique story, yet their experiences track right along with national trends.

All these choices are value laden, and yet they aren’t mere matters of personal preference. They neither start nor end with me. We are part of these large historical currents that move us. Even what counts as “traditional” changes over time. We don’t choose values like produce at the grocery store; more often than not, we are seized by them, possessed by them, carried away.

We are generic anybodies, until the accidents of life and history take hold, and suddenly things matter to us that never mattered before. And things that once mattered float away.

Thus we are left with two opposing but equally valid truths for what matters in modern life:

It’s up to you to decide what matters in life.

Life teaches you what matters.

Which brings us to 1950s Oxford.

The boo-hurrah theory of ethics

In his book The Women Are Up to Something: How Elizabeth Anscombe, Philippa Foot, Mary Midgley, and Iris Murdoch Revolutionized Ethics, Benjamin Lipscomb tells the story of four British women thinkers who stood, in their own ways, as a kind of resistance against the predominant “morality talk is meaningless” school of thought that emerged in Oxford during the mid-20th Century.

The view they opposed goes by various names like emotivism or the “boo-hurrah” theory of ethics. (A related idea is the fact/value dichotomy, the proposed inability to derive any “ought” from “is.”)

In this view, ethical statements are merely emoting, an expression of personal preference. And, the thinking goes, emoting may be many things but it isn’t rational. And it isn’t objective. Good and bad aren’t out there in the world, but rather individual subjective preferences. To say something is right or wrong is simply to say “boo!” or “hurrah!”—not to claim a truth. (Perhaps incoherently, in this conception, truth claims have more value than emotions.)

Lipscomb describes several Oxford philosophers through the 20th Century who held this view: A. J. Ayer, J. L. Austin, Gilbert Ryle, Richard Hare.

Richard Hare writes, “I have myself chosen, as far as in me lies, my own way of life, my own standard of values, my own principle of choice. In the end, we all have to choose for ourselves; and no one can do it for anyone else.”

This take continued on in the thinking of public intellectuals like Richard Dawkins and Stephen Jay Gould. Gould wrote, “It’s a tough life and if you can delude yourself into thinking that there’s…some warm fuzzy meaning to it all, it’s enormously comforting.”

Twentieth Century existentialism (embodied in Jean-Paul Sartre) came to roughly the same view by a different route. In existentialism, there’s no rational basis for morality or value. The individual must simply choose and then live according to their chosen values.

This view has continued on into contemporary ethical philosophy as well. Philosopher Brian Leiter, influenced by Jonathan Haidt, argues essentially a deterministic version of this: Conflicts in morality are due to differences in individual physiology; morality comes from the individual, though the individual doesn’t have a choice in the matter.

Lipscomb argues that there’s not much difference between Sartre and the position of a contemporary Kantian like Christine Korsgaard. Lipscomb writes:

Korsgaard doesn’t speak, as Hare did, of “principles” and “duties.” But she does speak of “obligations,” and traces them to acts of self-commitment. We adopt “practical identities,” she says—self-conceptions—and build our lives around them. Once we’ve done so, the burden falls on us to live up to our chosen identities. An obligation is the perception of a threat to some identity you’ve embraced. If you conceive of yourself as someone’s friend, for example, you will have notions of what behavior fits or doesn’t fit with that identity. The pained awareness that your friend’s birthday is approaching and you haven’t sent a card: that’s the force of obligation. But all of this exists, Korsgaard insists, only from “the first-person perspective.” We cannot be wrong about ethics—only inconsistent. We can, at worst, fail to live up to the identities we’ve embraced.

The reality of evil

Anscombe, Foot, Midgley, and Murdoch were each fiercely independent thinkers, so they weren’t quite a “school” of thought. But they were all moral realists, and in this way they opposed the dominant Oxford school of positivism and ordinary language philosophy posed above, and laid the groundwork for the contemporary revival of virtue ethics.

For all of them, thinking clearly about ethics required paying close attention to the kinds of creatures we are, our psychology, our way of life. You weren’t going to get there simply through logic or clinical linguistic analysis. But that didn’t mean values weren’t there.

In a way, both sides of the debate were directly and indirectly responding to World War II. The absurdity of wartime led many to the view that all this talk of principles, ideals, and values was bullshit. At the same time, the horrors of Nazism stirred many toward an even stronger moral sense. Evil was real. And any attempt to turn it into mere personal preference couldn’t last a minute outside the walls of academia. Lipscomb writes:

Murdoch’s judgment on Ryle could be applied equally to Austin: his world was one, she wrote, “in which people play cricket, cook cakes, make simple decisions, remember their childhood or go to the circus; not the world in which they commit sins, fall in love, say prayers, or join the Communist Party.”

Mother and child

What they ended up with was, at least, a beachhead for ethics in the modern world based on our biology, our animal-creature-ness, without appeal to God or revelation or reason.

If modern science affirmed a “billiard ball” theory of the universe, in which everything that exists is merely mindless atoms banging around in a void with no purpose, it also gave us a greater appreciation for our biology. One small example: We are mammals. And what do mammals do? They nurse their young. This places the mother and child — the sacrificial love of another and the receiving of sacrificial love from another — as essential to our existing at all. Not for every possible kind of creature, but the kind of creature we are. And, moreover, it is not a principle, idea, or conception we might debate or even need to conceptualize or verbalize but a value indistinguishable from our form.

Our universe may be pointless and absurd, but the will to love gives us meaning in spite of it all. This is the cultural mythical narrative we tell over and over again, especially in epic movies. And it is, perhaps not coincidentally, an attempted reconciliation of two modern philosophies of value.

“I got bored one day and put everything on a bagel…”

Related:

My personal sumpathies are with the women rather than with the positivists, but It just seems a bit empty doesn't it? To the extent our values our innate, they don't need to be questioned. To the extent they can be questioned, they're not innate.

This was a wonderfully written post. But what would these philosophers say about the innateness of evil? For just as sacrificial love seems like a fundamental part of being a mammal, so is cruelty, the will to dominate, the impulse to fight and crush and exploit--these things are part of us, too. To derive our ethics from our nature seems inconsistent with the idea that ethics is a way of resisting our lower natures--which is at the heart of so many ethical teachings.