Jonathan Franzen was right about the climate crisis

He was only five years ahead of the consensus

The Book:

What If We Stopped Pretending?

By Jonathan Franzen

4th Estate

2021

The Talk:

This winter we had blizzards that were more wind than snow. One blizzard left a layer of red dirt on everything, blown up from the far south. All spring we had dusty skies, and when a tornado came through the weatherman remarked on how large it looked due to all the dust. On another windy day we had something like a dust storm that turned the whole sky gray-brown. Then came the Canadian wildlife smoke, about a month later than usual, once again from record-breaking fires in the north. The North America summer forecast this spring projected a season significantly hotter than average, significantly drier than average, with fewer clouds than average. On relatively cooler days, we get air quality warnings for the Canadian smoke; on hotter days, we get excessive heat warnings. Yesterday the heat index was 115 degrees.

In 2019 American novelist Jonathan Franzen published an essay in The New Yorker entitled “What If We Stopped Pretending?” In 2021 the essay was published as a thin hardcover with a forward by Franzen and a German interview that prompted him to write the essay.

His argument was simple: Avoiding catastrophic climate change is no longer possible. By focusing all our attention on an unwinnable fight, we draw attention away from other environmental (and social) issues that are solvable. We should still work to decrease our carbon emissions, but because catastrophic climate change is now unavoidable, we should focus on other problems as well, in preparation for a chaotic future.

If you’re younger than sixty, you have a good chance of witnessing the radical destabilization of life on earth—massive crop failures, apocalyptic fires, imploding economies, epic flooding, hundreds of millions of refugees fleeing regions made uninhabitable by extreme heat or permanent drought. If you’re under thirty, you’re all but guaranteed to witness it.

The essay was publicly criticized by many climate activists as essentially surrendering the fight against climate change. (This Vox article summarizes the fury.)

As far as I can tell, the cause of Franzen’s personal frustration is that he is obsessed with birds. And that has meant he’s spent a lot of time around environmentalists and conservationists. And he’s annoyed that over the course of thirty years the climate issue has grown to dominate the environmental and conservation discourse. His basic attitude is: There’s no point obsessing anymore about climate. We aren’t going to stop it or solve it. So let’s get back to talking about birds.

“All-out war on climate change made sense only as long as it was winnable,” Franzen writes. Now the shift should be to a “balanced portfolio” of short, medium and long-term projects, including the strengthening of social and economic institutions for the disasters to come.

In the Germany interview, Franzen gives the example of a telling a heavy-smoking friend to stop smoking1. In one version, you tell him to stop smoking because it’s shortening his life, and you want him to live as long as possible. In the other version, you tell him, “If you stop smoking, you will never die.” In Franzen’s view, that’s the climate activist position, claiming that the problem can be solved vs. marginally improved around the edges. Fewer miserable days, while it lasts. That’s what we should reasonably expect.

Climate realism

It only took five years, but in April David Wallace-Wells wrote a piece in the New York Times titled “The World Seems to Be Surrendering to Climate Change.”

Just a few years ago, worldwide climate concern seemed to be reaching new peaks almost monthly, with cultural momentum growing and policy commitments following. Then came Covid, inflation and higher interest rates, which made the cost of living and global debt crises worse — and above all, perhaps, a new accommodation to the brutal realities of climate change that some call pragmatism and some normalization.

European leaders are rethinking their commitments to green energy in light of Ukraine. Canada has repealed its carbon tax. Mexico, whose president is a climate scientist, is building out fossil fuel infrastructure. (I would add, under the Biden administration, U.S. oil production reached record highs.) The business and banking world is also in retreat:

Over the past year, the [Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero] has added fewer than 10 members, and since December, it has lost BlackRock, JPMorgan Chase, Goldman Sachs, Wells Fargo, Citigroup, Bank of America and Morgan Stanley. The S&P Global Clean Energy Transition Index has been in steady decline, the energy analyst Nat Bullard recently noted, with its value falling by more than half since 2021.

Wallace-Wells mentions that the Council on Foreign Relations (the most elite group of old establishment types in America2) launched a “Climate Realism” initiative this year to “prepare for a far more punishing 3 degrees or more.”

The one bright spot that Wallace-Wells pins his hope on is the green energy transition. Both solar and wind energy use have been growing globally. The data points on their face seem miraculous.

…worldwide annual solar power installations having more than doubled since 2021, annual global investment in the energy transition doubling to $2 trillion in just three years, renewables producing 92.5 percent of added worldwide power capacity last year. And although a staggering share of that global progress is taking place in China, in the United States the progress can be similarly breathtaking: wind capacity up 23-fold in two decades, according to a new analysis in Vox, utility-scale battery capacity up 29-fold in just five years and more U.S. electricity generated from clean sources than from fossil fuels this March, for the very first time.

Surely, if these numbers are true, we are on our way to solving the climate crisis. If nothing else, we have hope because the solution is happening already, we just need to scale it.

And yet there’s a nagging feeling that something isn’t quite right.

No transition

The argument from activists has been that a better future is possible through an energy transition. The story is easy to understand. Civilization used to run on wood, then it ran on coal, now it runs on oil and natural gas. All we need to do is to get it to run on solar, wind, hydro, thermal, and nuclear. Step 1) Electrify everything. Step 2) Transition to renewables.

In June the Financial Times published a feature titled “Why the world cannot quit coal.” (There’s a nice non-paywalled version here.) Coal is the worst form of fossil fuels that we burn. It’s widely agreed that even switching from coal to natural gas would be an improvement. Any energy transition must mean less coal being burned and eventually no coal being burned.

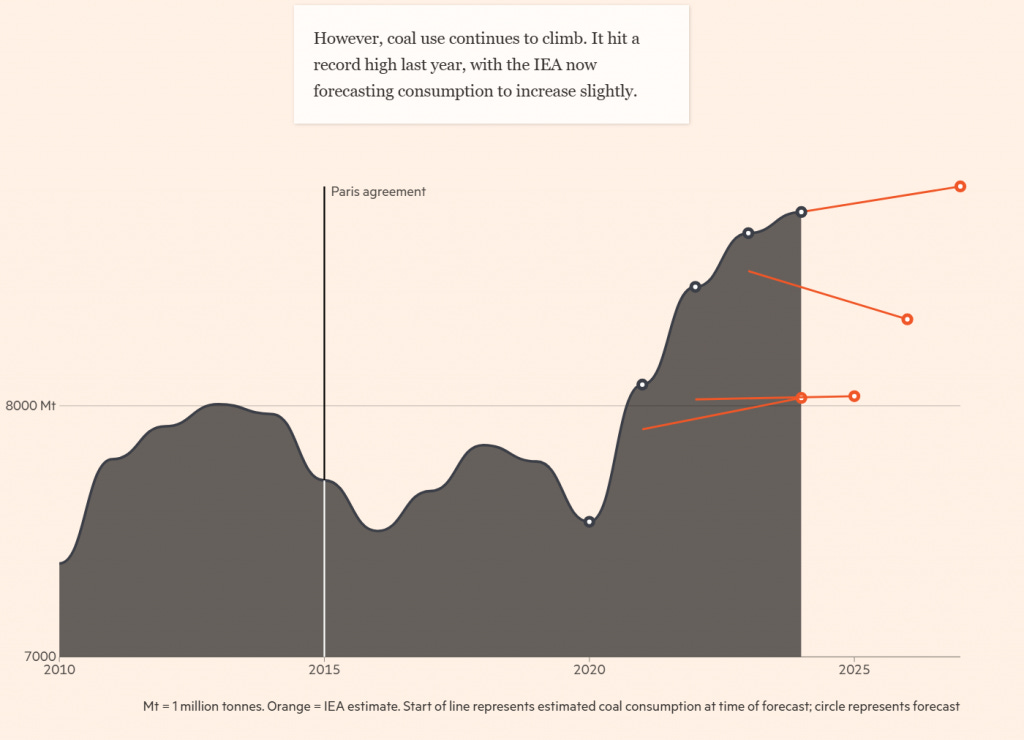

In 2020, the IEA declared that global coal use “peaked” in 2013. Then we exceeded that peak. And have continued to increase every year since 2020. The IEA has continued to predict a peak or flattening, and they continue to be overly optimistic. Each red line in the graph below marks a predicted path for coal that the IEA made.

One group of forecasters who reviewed the IEA’s record on coal, found that it consistently underestimated coal demand and predicted that there is a 97 per cent chance that Chinese coal consumption in 2026 will be greater than the IEA’s forecast.

The world now burns double the amount of coal that it did in 2000. And the best bet is that that number is going up.

So how do we square, over the same period, (a) record-breaking renewables coming online and (b) record-breaking fossil fuels coming online? Moreover, how do we square these in places like Texas and China, who are massive producers and consumers of both renewables and fossil fuels?

The world’s energy needs are growing so quickly that the world simply needs more of everything, says [Sir Dieter Helm, professor of economic policy at Oxford university] — more renewables, more nuclear, and more oil, gas and coal. “Very sadly, there isn’t a transition” away from fossil fuels and towards renewable energy, he says — instead, it is an increase, in all directions.

This is also the conclusion of historian Jean-Baptiste Fressoz, author of More and More and More. In the 19th Century, when Britain was in its “coal era,” it consumed more wood than it did before coal, by using wood to build mine shafts. Today’s “oil era” depends on steel which must be made with coal.

In short, historically, there are no transitions, there’s just more consumption. And new technologies lead to greater use of all other resources. Long after the era of “wood” we consume more wood than ever. Long after 19th Century soot-covered cities, in an era of nuclear power, solar panels, and wind turbines, we consume more coal than ever3.

Betting on wildcards

Electrifying everything and rapidly transitioning to renewable energy is the only practical plan on the table. If that’s gone, a realistic shot at keeping the world we have is gone too.

Beyond that is flights of imagination. Degrowth, government imposition of unpopular taxes or laws, carbon capture and storage, geoengineering, or the belief that we can “cross the line” into chaos and pull ourselves back to safety decades from now—the plausibility of any of these depend on your intuitions about human nature. (Intuitions about technology are fundamentally intuitions about humanity—how it will respond, what it can solve, discover, build, deploy, and overcome, and at what speed it can act collectively.)

If you believe in the potential of humans to come together and solve any challenge, then you’re optimistic about the climate. If you’re cynical about human nature, you’re cynical about climate. I think strong cases can be made for both sides, but we are no longer discussing the climate crisis.

Beyond imagination is chance. One can shrug and say “anything is possible” and “the future is never certain.” But that, too, applies to everything, and, thus, could be said about your plans for tomorrow. A miracle could happen tomorrow, but that’s no evidence or argument that it’s reasonable to believe it will, or to plan on or expect one.

It’s later than we thought

So where does that leave us?

If there will be no rapid and orderly transition away from fossil fuels, then we are facing down several decades-worth of chaos in every region of the world, across every dimension:

Health: Water shortages; heat wave mass casualty events; poorer air quality; smoke, dust; wider spread of tropical diseases; degraded human cognition and mental health

Agriculture: Global drought, increase in pests and crop disease; plants become less nutritious; higher arsenic levels in rice; lower crop yields and food shortages

Property: Wind, flood, and fire destruction of communities; super-hurricanes; the retreat of property insurance; coastal property loss due to rising sea levels

Governance: Increasing violent crime due to heat; unprecedented mass migrations; destabilized governments; increased risk of wars; conflicts over water

Economy: Canals and rivers used for trade drying up; higher utility bills; increased food costs; supply chain disruptions due to disasters

Technology: Frequent blackouts; planes unable to fly; days too hot for wind or solar farms to operate; hydropower declining due to drought; nuclear power also in danger due to drought

Nature: Animal extinctions, habitat loss; loss of natural wonders, glaciers, rainforests, and reefs; desertification

Culture: The loss of historical and heritage sites; destruction of cultural sites and artifacts in flood, fire, and sea level rise; breakdown of communities as result of displacement to other regions

How exactly all these things will happen, and how they might interact with each other, are unknown. But they are already happening now and getting worse now.

World news rarely breaks through into U.S. media. But in this summer alone China has had its electrical grid pushed to the max multiple times under a record heat wave; Pakistan has experienced catastrophic flooding due to rapid glacier melting; Tehran is experiencing dwindling water and an electricity crisis under extreme heat; Turkey set a new record high temperature (122.9F); southern Europe has experienced multiple heat waves, causing thousands of deaths and bringing wildfires to the gates of Marseille.

The situation will be worse than this five years from now. And it will continue to get worse for decades to come, everywhere.

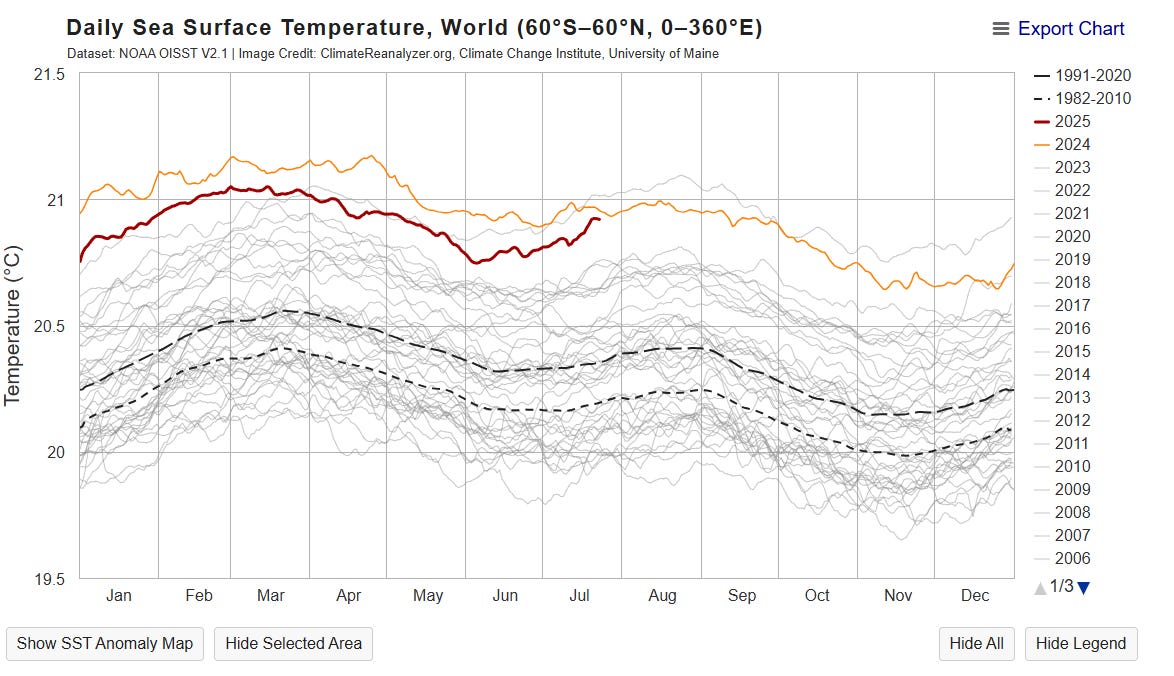

The situation has even darkened notably since Franzen’s fatalism in 2019. Starting in the spring of 2023, surface and sea temperatures jumped dramatically—and have not gone back down to pre-2023 levels since. Scientists are unsure why.

Around 2020, climate scientists said there was a chance we might cross 1.5 degrees briefly before 2030. By 2024, however, we reached 1.6 and are likely to cross 1.5 again this year. And some predict we are going even higher before the decade is out. We may be a decade ahead of where climate scientists in 2020 thought we would be. That’s only five years ago. Climate change is accelerating, with record high emissions and record high CO2 levels as we speak4.

Into the storm

You can call it doom if you want or the end of the world. But this seems to lead to nothing more than sophistic cocktail party debates about what “the end” really means and “when” exactly it will be the “end.” Or it leads to debates over how many billions of suffering humans are acceptable to you from the comfort of your armchair. None of that changes the physical reality.

It’s easy to sit around and come up with a story about how things actually turn out just fine. But whatever story we invent about future “adaptation” always seems question begging to me, as if all the above can happen but:

Scientific research continues unabated (which requires healthy humans and stable institutions and societies)

AI and the internet remain unaffected (data centers run on water and electricity and must be continually cooled)

Microchips keep getting shipped (Copper mining requires pure water)

Global trade and economies of scale remain intact (what makes things cheaper over time and allows for distribution of new technologies)

Consumption levels remain high (sans food and water)

Silicon Valley and Wall Street (one in California, the other at sea level) are easily portable to somewhere new

Society won’t collapse, the logic goes, because society will be there to prop it up. But nobody finds solace that they won’t die because, if their life was ever at risk, they would do something about it. In both cases, everything depends on doing enough in time, which is the nub of the problem itself.

To feel anxious, depressed, grief-stricken, shocked—all these seem like completely reasonable and normal responses. As do feelings of rage, resistance, boldness, and heroism. What to do with those feelings on any given Tuesday under a mild sky is an open question.

But I don’t think the rest of Franzen’s argument, how we should respond to the (barring a miracle) inevitable, is sufficient for everyone. Humanity is not one thing, and humans should not all receive the same prescription. The “right” response is as manifold as human life. A “balanced portfolio” is one approach. But when faced with danger, some people take bigger risks, some take fewer risks. Sometimes people bond closer together to survive, sometimes social bonds are broken for the sake of survival (as in the case of famine). Most of these actions are instinctual.

I don’t know what “should be done,” though my gut says: Everything. Everything should be done. Every option should be tested. Every unknown should be investigated. Every preparation made. Everything, on every level, in every direction. Far, far more than we are doing now. And certainly not going in reverse.

Related:

Climate change is my family's life now

Burning down the memory palace

Climate diaries: Real and imagined

Global drought impacts detailed in new report by NDMC and UNCCD5 (University of Nebraska)

I’ve always found the smoking/drinking analogy to climate a bad metaphor in a critical way. You would have to imagine that alcohol and cigarettes were not only destroying their health but also essential to their prosperity. The Picture of Dorian Gray is a better analogy. Or perhaps living on a credit card in which your purchases make your life better while also making your overall situation more dire.

See also Vaclav Smil’s 2015 lecture “Energy Revolution? More Like A Crawl”: “We are a fossil fuel civilization. We shall remain so for a long time to come… Innovation is overvalued and exaggerated. We are still living in the world of the 1880s.”

The distinction between emissions and CO2 is important. CO2 rose at a record rate last year, but the rise in human emissions does not fully account for it. Natural CO2 emissions are now rising alongside human emissions in ways we do not fully understand and certainly can’t control.

“‘This is simply not just another dry spell,’ [Mark Svoboda, report co-author and NDMC director] said. ‘This is a global catastrophe covering millions of square miles and affecting millions of people, among the worst I've ever seen.’”

Geoengineering is the only viable solution to climate change at this point. Trying to reduce emissions enough to stop the disaster is wasting energy.

If I'm reading your graph on ocean temperatures correctly then 2025 temps dropped below 2023 levels back in March and remain lower.